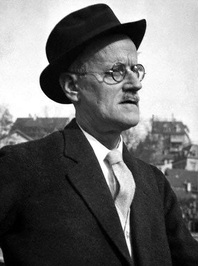

February 2nd, James Joyce’s birthday, is my favorite of literary anniversaries. It’s not just that he is one of my favorite authors, but he valued his birthday intensely and took great pains to arrange the publication of his two big books on that day. Ulysses was published on 2-2-22, which I’m sure pleased the author. Finnegans Wake eventually saw the light on 2-2-39.

So this February 2, I find myself thinking about what Joyce had to say about education and teaching. In Ulysses, the autobiographical Stephen Dedalus is a schoolteacher and teaches a half day of class before his Dublin peregrinations.

In one fine moment, he helps an awkward boy finish some math after class and imagines himself at the same awkward age:

“Like him was I, these sloping shoulders, this gracelessness. My childhood bends beside me. Too far for me to lay a hand there once or lightly. Mine is far and his secret as our eyes. Secrets, silent, stony, sit in the dark palaces of both our hearts: secrets weary of their tyranny: tyrants, willing to be dethroned.

“The sum was done.”

Stephen’s half day ends with him being paid by the headmaster, a tiresome, anti-Semitic blowhard who enjoys lecturing him. The headmaster senses that Stephen will not linger in this job and says, “You were not born to be a teacher, I think.” “A learner rather,” Stephen replies.

Teachers are, of course, lifelong learners, but so are those who devote themselves to writing as Joyce did, though after several years teaching English to Italian speakers in Trieste.

The headmaster replies, “To learn one must be humble. Life is the great teacher.”

What fascinates me is that this line is widely quoted as a prime Joycean quotation (check the internet), though anyone who knows Joyce knows that “humble” is not an adjective one would apply to him.

Joyce puts these “fine sentiments” in the mouth of a pompous bigot intentionally. Perhaps he intends to remind us of Shakespeare’s most quotable pompous ass, Polonius (“The apparel oft proclaims the man”; “Neither a borrower nor a lender be” etc.)

Indeed, earlier in the scene, Joyce shows the headmaster quoting Shakespeare as he praises the financial responsibility of the English. “But what does Shakespeare say? Put but money in thy purse.” “Iago,” Stephen quietly murmurs, recognizing (just as we should with the headmaster’s words about life) that the sentiment is hardly Shakespearean in feel; it was put into the mouth of his most notorious villain.

This reminds me of the controversy over the new ten-pound note released in the U.K. featuring Jane Austen. It offered this quotation from Pride and Prejudice: “I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading.” A fine Austen sentiment–until one realizes it is spoken by Caroline Bingley, who hated reading, and that Austen surely meant it to satirize Caroline’s flirtatious fawning.

Joyce and Austen repay close reading; they help make us “learners rather” by caring immensely about language. And that is useful to remember and go back to when we observe language being used with increasing carelessness and disingenuousness in our social media and by our political leaders.

In that light, one of my favorite lines in the schoolroom chapter of Ulysses comes when the headmaster intones righteously, “We are a generous people but we must also be just.” “I fear those big words which make us so unhappy,” Stephen replies.

Joyce was a master of language, conversant in many and fluent in English, Latin, Greek, Italian, French, and German. He learned Norwegian as a teen to write a letter to Ibsen. His writing weaves the language of the Dublin streets with parlor songs, Shakespeare and Dante, sentimental novels and dusty histories, clichés, and lyrical moments. But, as the quotation above hints, he cared deeply about how language was used to oppress and how it could be used instead to celebrate a human spirit and mercy over justice.